Originally published in Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management

COVID-19 taught Americans a lot of valuable lessons. Many organizations tried their best to provide the necessary supplies to mitigate the pandemic. In spite of that, lack of vaccines and shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) at the beginning made matters worse. At the time of this writing, there are more than 40 million cases and more than 692,000 deaths in the USA. For a rich country like the USA, this is a sad outcome.

Disasters have been classified in many ways. The level of difficulty for mitigating the disaster depends on whether there is a slow or sudden onset and whether the disaster is localized or dispersed (Apte, 2009). There seem to be other factors that interfere with the immunity of supply chain. We hypothesize that high availability of information at the beginning is feasible if the pandemic is localized, which in turn generates public trust. For a pandemic that is dispersed, thus involving people of all kinds, as the pandemic lingers the availability of accurate information from a single authority of truth goes down, and that creates lack of public trust. Figure 1 explains this concept.

Pandemics are often of slow onset and linger for a longer time. They can disperse quickly as the virus spreads or mutates, but vaccines can mitigate this spread and mutation. For this reason, the deaths in the USA pre-vaccine are understandable but not after the vaccine became available. As new information is provided by agencies and the media, we reach an optimal level of public trust, but as such information increases in variability over time distrust sets in. This distrust is not so much tied to lack of information as much as lack of verifiable accurate information (Figure 2).

Based on this framework, COVID-19 represents a disaster with a slow onset, yet one which is dispersed around the globe. Dispersion was largely a function of international travel, as infected passengers traveled from China to Southeast Asia, Europe, the USA and South America. Our analysis of supply chain disruptions, developed through Resilinc (https://www. resilinc.com/), a supply chain disruption tracking platform, shows the domino effect of COVID-19 on supply chains, as shown in Figure 3. One can observe how COVID-19 moved across the world and began to disrupt supply chains first in China, then Europe and into the USA. It eventually spread back to other areas like Southeast Asia. Variants of the virus, such as the South African and Indian (Delta) variant, also spread slowly and created a fourth wave in many Western countries, such as the United Kingdom and the USA.

During a pandemic such as COVID-19, the distribution and delivery of critical supplies and services to the affected population proved a major undertaking. Lockdown of factories and offices, export restrictions and rapid spread of the disease among workers in congregate settings created multiple shortages of medical products, particularly in areas where manufacturing assets did not exist for these supplies. Response supply chains for vaccines and PPE should be established in anticipation of pandemics and need to be robust. Unfortunately, governments did not provide adequate warning of the spread of the pandemic, resulting in significant medical shortages, overwhelming populations showing up in intensive care units and emergency rooms in hospitals and significant loss of life during the early months of the pandemic in many Western countries (Handfield et al., 2020).

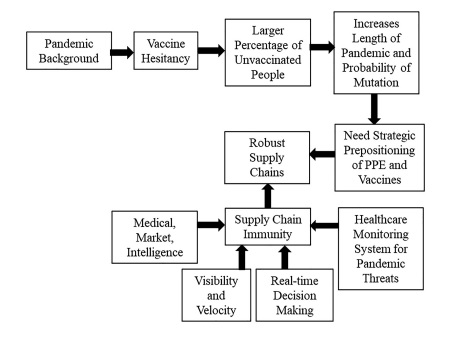

In this article, we examine one aspect of strategically “prepositioned” supply chains. Our primary objective is to review the experiences our team went through during COVID-19 and prepare a rationale for a new type of capability required to address such slow-moving, dispersed pandemics in the future. We define this capability as “supply chain immunity” and describe the characteristics of this capability in terms of what we observed was lacking in many humanitarian and government supply chain systems.

We introduce the attributes of supply chain immunity. Based on this, we suggest approaches for developing future supply chains in case of slow, lingering disasters such as epidemics or pandemics in the future.

COVID-19 impacted considerable humanitarian operations. We believe the concepts and model of “supply chain immunity” presented in our research are particularly important for humanitarian organizations to absorb, given that pandemics have spread worldwide due to lack of preparation and prepositioning. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as MSF (Medicins Sans Frontieres or Doctors without Borders) are one of the first organizations to help when local government organizations in an underdeveloped country are overwhelmed by such a large disaster. COVID-19 response took humanitarian response to a new level, resulting in a whole-of-world response from NGOs such as Project N95 and the Helena COVID-19 Network Project, global relief partnerships such as COVAX, the World Health Organization (WHO), military and governmental organizations in the affected country that get called in for assistance, like the Army National Guard in the USA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), state-level chief procurement and emergency management officers, the Defense Logistics Agency, Department of Health and Human Services and US Air Force Contracting (Handfield et al., 2020). All of these seemingly disparate organizations were working to address the shortages created by the pandemic concurrently but were not always aligned in the same direction. So, while there was a whole-of-world response, the effort was not coordinated with a whole-of-world strategy. We use our engaged scholarships findings, analysis and recommendations in this paper as an early guide to aid these parties in pulling the same direction the next time around.

Read the full article in Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.